Medical Databases

Contents

Group

The Prestidigitators:

- Sarah McCabe

- Brandon Schur

Introduction

As Canada struggles to bring its health care system into the modern era, governments have been examining ways to increase efficiency, lower costs, and improve patient care to “maintain a strong capacity to support the health, safety and economic well-being of Canadians” (1). Emerging technologies present many possibilities - specifically medical databases - in conjunction with the Internet to allow increased accessibility, timeliness, and usability while dealing with increasing content (1). Whether allowing for the standardisation and instant transmission of patient records from one jurisdiction to another, the diffusion of medical advancements across the nation, or the dearth of information made available for research, medical databases hold great promise for both the immediate present and the future.

Medical databases are not without their drawbacks, however. High initial and continuing costs, the requisite technical knowledge to use and maintain the systems, and privacy issues present significant hurdles to overcome (2). The issue of cooperation between separate and independent jurisdictions also remains especially relevant in Canada. In this article, we examine the feasibility of implementing a web-based nationwide medical database system and use the Calgary Health Region as a case study to come to our conclusion.

What Are Medical Databases?

Medical database systems can refer to many disparate systems with distinct functions. In addition to electronic health or patient records, journal databases, and virtual libraries of up-to-date information on advanced medical procedures and treatments, medical databases can also involve numerous other technologies. These technologies include tracking systems, computerized physician order entry systems, clinical decision support systems, drug interaction information or treatment models, and enhanced reporting systems that facilitate population-based health care models and more extensive outcomes research (1). Many other programs can be incorporated into a medical database, however, so the abovementioned functions are not exhaustive.

The Case For Nation-Wide Medical Databases

Recently in Canada, the federal government has identified the need to provide employees in government departments, including Health Canada, access to the information they need to work “efficiently and productively” (3). For this reason, government is currently investigating a “Federal Science eLibrary [that] aims to deliver seamless and equitable access to full-text electronic journals in science, technology and medicine (STM) to the desktops of all federal government researchers, policy analysts and decision makers” (3). Having each department negotiate for its own distribution rights and licenses results in duplication of effort and inefficiencies, and current library spending is insufficient to keep up with rapidly advancing technology. A single digital research database, potentially accessible through a web-portal, is thus an appealing means to boost collaboration and the access of information (3). Additionally, “Investment in digital access to electronic journals will yield excellent value and result in better use and management of public funds,” (1), according to feasibility studies. A 2006 pilot study found that, “80% of survey respondents indicated… a positive or very positive impact on their research activities and productivity. 71% of impact survey respondents used the tool several times or more per month” (4). Such results are promising for the usefulness of scientific (and medical) database technology. Not only government would boon from this initiative, however, as private research institutions and universities could benefit as well.Hospitals too stand to gain much from the implementation of database systems. In fact, in the United States, the Institute of Medicine is urging lawmakers to invest in “information infrastructure to support health care delivery, consumer health, quality measurement and improvement, public accountability, clinical and health services research, and clinical education” (2) by intersecting numerous different health care-related technologies. Medical database systems allow for the elimination of handwritten instructions (to help fight against medical error), the tracking and recording of patient treatment and encounters, analysis of the success of prescriptions or treatments, and the fast retrieval of patient medical and billing information to name just a few systems (2). Furthermore, increased patient safety, faster access to information, increased availability of information in rural areas or for smaller organizations, and heightened coordination are all benefits associated with large-scale medical database technology (5). Already, recent medical graduates especially are using online medical tools (6), implying that online medical systems are quickly becoming the norm and their usefulness widely recognized.

Another benefit that large-scale patient record databases offer is the ability of researchers to analyze the effectiveness of certain drugs or procedures by running directed searches (7), or to select patients for study based on certain properties that are of interest (8). Such studies allow hospitals to use the best treatment options and reduce workload, resulting in satisfied patients and doctors. Oracle database systems, for example, have been used in the US “to gather and mine reliable patient data to support [best] practices” and improve patient outcomes, “update [practitioners’] knowledge through continuous research on the finest medical and nursing science proven practices,” and measure hospital performance (7).

Criticisms

Perhaps the greatest barrier to overcome, and thus the greatest criticism of medical database technology, is cost. In one report, the authors explain that, “the health care industry will have to adjust to costs associated with evolving technologies and short system-lives” (2), which is a significant hurdle for the already cash-strapped Canadian health care system.

Although medical databases ease the flow of information, this ease of transfer also raises certain concerns for many experts. Firstly, there are worries that both the accessibility to various users and size of such systems, as well as the ethical obligation of medical practitioners to record patient encounters, could in fact jeopardize the confidentiality of patients (2) (9). While confidentiality concerns could in part be assuaged through strict controls, such controls would by necessity limit the usefulness of patient records for such uses as population-based research. Policymakers must therefore carefully consider this delicate balance of functionality versus patient privacy rights.

Furthermore, the ownership of patient records could potentially be compromised by the deployment of proprietary database systems and could thus actually impair access to information and patients’ privacy (10). Proprietary systems also run the risk of a small number of companies monopolizing the technology and hardware necessary for interoperability, which would further compound the issues associated with compatibility between different systems (2). Already, the issue of different systems to reflect diverse jurisdictions and varying medical practices make the prospect of a nation-wide database system difficult enough to design: “Since medical care itself is not standardized, it remains difficult to envision a “one size fits all” approach” (2). Ownership over records, technology, and varying medical practices combine to complicate the process of implementing a large-scale database system across the country.

Some controversy already stems from certain databases that now make patient records or health information available online; some even aggregated by the patient him- or herself. Private companies offering such technologies are often derided as being “immature,” impermanent, and even functionally limited (2). This is a concern when “the quality of medical information is particularly important because misinformation could be a matter of life or death” and “the quality of information on the internet is extremely variable” (11). Regardless of whether the public or private sector administers a medical database, the quality management protocols put in place are of the utmost importance (12), and must be regulated or otherwise controlled by government to mitigate these risks.

Eclipsys™ Sunrise Clinical Manager (NASDAQ: ECLP)

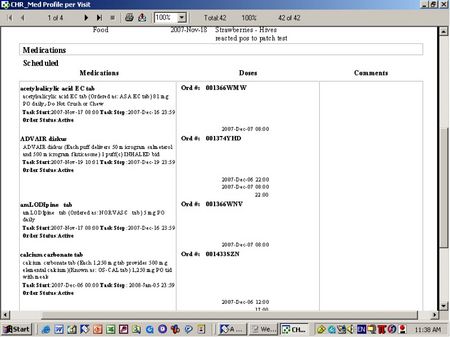

“Eclipsys is a leading provider of information solutions that help hospitals and health systems more-effectively manage the business of healthcare and achieve measurable and sustainable, improved outcomes.” SCM has become a pivotal tool, in conjunction with other prestigious software programs (See: Logibec Clinibase) for ease of administration and communication between all members of a health care team; doctors, nurses, managers, educators, and staff alike. The underlying Eclipsys XA™ architecture and ObjectsPlus/XA™ application development technology are what provide the structure for the program the CHR employs, but the rest is up to the Region’s IT staff to customize and make compatible the program to cater to Calgary’s specific needs. Together with eLink – the Eclipsys EAI development tool – ObjectsPlus/XA enables Eclipsys clients to integrate with third-party applications (See: Logibec Clinibase).

Primary Functions

SCM serves the following primary functions:

- Retrieving current and historical patient care records

- Conducting administrative functions such as patient admissions and retrieving information on emergency contacts

- Ordering drugs for patients

- Booking rooms and procedures

- Billing insurance or provincial health care plans

- Giving "orders," or instructions, to health care providers such as and when and how often to administer drugs to a patient

- Gaining access to a virtual library of leading-edge technology and medical procedures

All of these points serve to prove the vast capability of this particular database program.

Advantages

- Cost efficiency - As seen in the case study (See: Case Study: Calgary Health Region below), SCM comes at a comparatively low cost (See: Sources; Calgary Health Region Annual Report 2008).

- Time efficiency - Input and output of information and actions on SCM is proven to be 45%-90% more time-efficient than any previous convention, such as writing the order in a chart and then using a phone or paging system to communicate the event.

- Ease of communication- that is, barriers of space and time no longer apply as long as the sending and receiving parties have access to a computer equipped with SCM and/or the local printer from which the print copy of the event is produced.

Documented Outcomes as retrieved from the Eclipsys website (See: Sources; Eclipsys Sunrise Clinical Manager website):

- 100% physician adoption of order entry at a community hospital — Piedmont Hospital, Atlanta, GA

- 66% reduction in medication administration errors — DeKalb Medical Center, Decatur, GA

- 43% reduction in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia — Springhill Medical Center, Mobile, AL

- Nearly 50% decrease in Accounts Receivable days — Community General Hospital, Syracuse, NY

Disadvantages

- Server Crashes - Although few and far between, in the event of a server crash, IT personnel have to work quickly and effectively to get the program running again. In the event of a server crash, all information is locked and inaccessible, but never lost entirely. Necessary documents for carrying out actions that normally would have been transmitted become necessary, and all actions passed during the crash must be input when the server is back up.

- Lack of Rapport - Like e-mails or text messages, there lacks immediacy, tone, body language, etc. which occurs within face-to-face human interaction. Although there are elements of the SCM program which allow the user to convey different levels of importance (the red-yellow-blue priority flag system, for example), this experienced user of the program can say for the record that no matter how effective and efficient the program may be, there is always room for miscommunication.

- High Maintenance - despite it's low relative cost (See: Costs), SCM requires dozens of full-time Information Technology professionals to constantly de-bug, monitor, and troubleshoot 24 hours a day. In addition, educators/instructors are also needed to teach hospital/clinic workers how to use the program; this can be a lengthy process, depending on the depth of use of the individual worker.

- Redundancy - Through the connection with a local printer, a paper version of every transaction ever made on SCM is printed immediately after the action is finalized, so many health care workers may potentially struggle to keep up with modern technology and language. Still many others feel that a digital plus a physical copy of every transaction is redundant and wasteful. A solution to this may be to establish recycling services which safely dispose of confidential information.

Case Study: Calgary Health Region

The Calgary Health Region began as the Calgary District Hospital Group in 1891 and consisted of 1 hospital, the Holy Cross Hospital, with 4 beds and a staff of nuns from the neighboring St. Mary’s Cathedral. In its 117-year history, Calgary health care has grown to support a population of 1.1 million (2008 census). The Calgary Health Region employs thousands of staff, doctors and nurses to keep up with the largest metropolitan city between Vancouver and Toronto. The CHR administers to the following surrounding districts: Airdrie, Banff, Black Diamond, Canmore, Carmangay, Claresholm, Didsbury, High River, Nanton, Okotoks, Strathmore and Vulcan.

The Calgary Health Region adopted the use of the Eclipsys Corporation® Sunrise Clinical Manager medical database program on February 8, 2007.

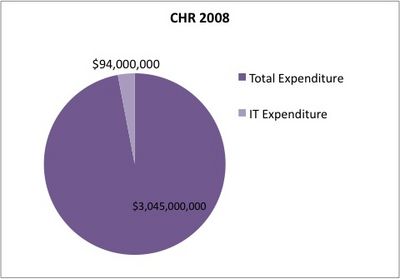

In 2008, the Calgary Health Region spent $94 million on Info Technology. Most of this is the cost of the Patient Care Information System, such as SCM and affiliated programs, which is less than 5% of Annual costs (See: Figure 1)

Figure 1: Calgary Health Region 2008

Conclusion

Taking into consideration that increased efficiency, improved patient care, and the potential for reduced costs in the long run, we feel that the benefits of medical database technology far outweigh the downfalls. Although we acknowledge that issues such as privacy and quality concerns, as well as cost, training, and maintenance need to be overcome or reduced, we feel that increased digitization and standardization of medical functions will help bring Canada's health care system into the 21st century. This will benefit all Canadians.

Judging by the wealthy but short history of medical databases, it would seem that digital patient care records and administrative systems belong to the natural progression of medical, corporate, economic, and even cultural evolution. The fact that with each passing fiscal year, more and more health care agencies - private, semi-private, government-based, and even military-based (14) - across the world (with Canada near the leading-edge(13)) are resorting to digital technologies to bring their health care operation and communication systems into the 21st century is no surprise.

The future of medical database technology is as bright as it is impossible to predict. Perhaps Canada, or even the world will adopt, on a macro scale, what Alberta is planning to adopt on a micro scale: a province-wide Patient Care Information System (13) (although this decision has not been finalized as yet, it may be Eclipsys) to allow for patient information accessibility for health-care providers, no matter which hospital or clinic that patient may visit.

Sources

Brandon:

1. Government of Canada. (2004). Federal Science eLibrary, Building the STM Knowledge Infrastructure - Executive Summary. Retrieved from the Internet on November 23, 2008, from: http://safstl-asbstf.scitech.gc.ca/eng/study/feasibility/summary.html.

2. Gunter, T. D., & Terry, N. P. (2005). Journal of Medical Internet Research 7(1) e3, The Emergence of National Electronic Health Record Architectures in the United States and Australia: Models, Costs, and Questions. Retrieved from the Internet on November 23, 2008, from: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/html/1807/4737/jmir.html

3. Government of Canada. (2006). Federal Science eLibrary, Access to the world’s scientific information through an interdepartmental initiative. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://safstl-asbstf.scitech.gc.ca/eng/initiative.htm

4. Government of Canada. (2006). Federal Science eLibrary Pilot Project Final Report, Executive Summary. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://safstl-asbstf.scitech.gc.ca/eng/report/final/fsel_rpt_summary.html

5. Canadian Health Libraries Association. (2008). Canadian Virtual Health Library, Feasibility Study and Readiness Assessment. Retrieved from the Internet on November 23, 2008, from: http://www.chla-absc.ca/nnlh/cvhl-feas.pdf

6. Frémont, P., & Lacasse, M. (2006). Canadian Family Physician vol. 52, Web-based tools. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://www.cfpc.ca/cfp/2006/oct/vol52-oct-college-janus.asp

7. Oracle Corporation. (2008). Oracle Customer Case Study, Aurora Health Improves Patient Outcomes through Business Intelligence. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://www.oracle.com/customers/snapshots/aurora-healthcare-db-case-study.pdf

8. Frize, M., Nickerson, B., Solven, F. G., & Stevenson, M. (n.d.). Computer-Assisted Decision Support Systems For Medical Applications. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://www.sce.carleton.ca/faculty/frize/hungmed.htm

9. Pincus, H. A., Simon, G. E., Unützer, J., & Young, B. E. (2000). American Journal of Psychiatry, Large Medical Databases, Population-Based Research, and Patient Confidentiality. Retrieved from the Internet on November 25, 2008, from: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/157/11/1731

10. Kohane, I. S., Mandl, K. D., & Szolovits, P. (2001). BMJ, Public standards and patients' control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private. Retrieved from the Internet on November 25, 2008, from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1119527

11. Eysenback, G., & Diepgen, T. (1998). BMJ, Towards quality management of medical information on the internet: evaluation, labelling, and filtering of information. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/317/7171/1496?view=full&pmid=9831581

12. Goldsmith, C., Holbrook, A. M., Kerby, J. P., Keshavjee, K., Langton, K. B., Levine, M. A., MacLeod, S. M., & Sebaldt, R. (n.d.). Centre for Evaluation of Medicines, The Feasibility of Using Electronic Medical Records to Advance Evidence-based Prescribing. Retrieved from the Internet on December 4, 2008, from: http://www.compete-study.com/documents/The_Feasibility_of_Using_Electronic_Medical_Records_to_Advance_Evidence-based_Prescribing.pdf

Sarah:

13. Calgary Health Region website -- http://www.calgaryhealthregion.ca

14. Eclipsys Sunrise Clinical Manager website -- http://www.eclipsys.com/

15. Health Alberta Annual Report 2008 -- http://www.health.alberta.ca/resources/publications/Annual-Report_08-Calgary.pdf

16. Patent/Family Safety Council of Alberta Annual Report 2008 -- http://www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/qshi/patientsafety/pt_family_safety_council/resourses_links/PatientFamilyAnnualReport08.pdf

17. Calgary Health Region Annual Report 2007-2008 -- http://www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/newslink/publications/index.html

18. Calgary Health Region: Quick Facts Pdf Link: http://www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/corporate/about_us/index.htm

19. Calgary Health Region: Map Of The Region Pdf Link: http://www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/corporate/about_us/index.htm

20. Slack, M. "Long Term Care - Memo." Retrieved from the Internet December 4, 2008 from: http://search.calgaryhealthregion.ca/search?q=cache:P6YIbl3eUXMJ:www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/programs/pharmacy/resources/longtermfiles/ltcscmreports.doc+sunrise+clinical+manager&access=p&output=xml_no_dtd&ie=UTF-8&client=default_frontend&site=Region&proxystylesheet=default_frontend&oe=UTF-8